Christian Fantasy and the Tree of Life

I’m always on the hunt for excellent books to provide my voracious readers with new adventures that will point their hearts and minds to truth. So when two friends recommended the same series to me in one week, I bought the first book on Audible. My children were instantly intrigued with The King of the Trees, a fantasy world that’s part Middle Earth, with hints of Narnia and the humor of The Tales of Larkin–woven with rich Biblical allegory and memorable poetry.

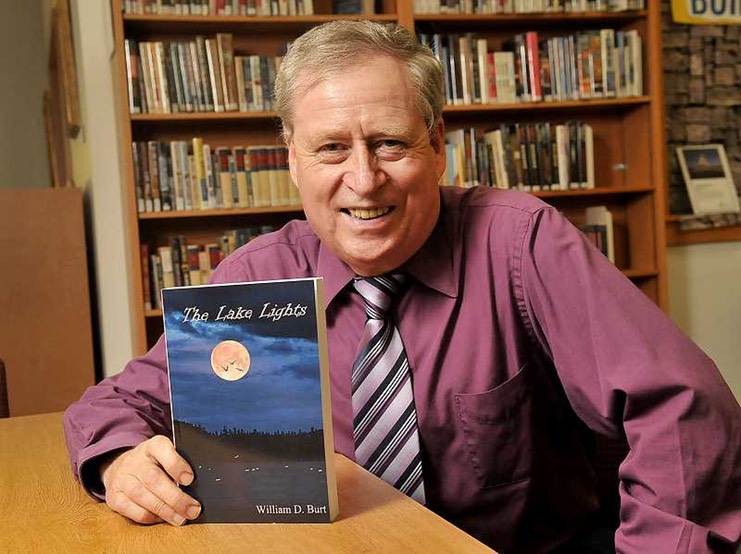

Before I knew it, my children were writing fan letters to the author, William D. Burt, and begging for more of his books. They were thrilled to discover The Lake Lights. Part Jonathan Park, part The Truth Chronicles, the Creation Seekers series has my children discussing dinosaurs and talking in a Scottish accent.

I’m delighted to introduce you to William D. Burt, a man who is passionate about writing fantasy that inspires and develops the moral imagination.

An Interview with William D. Burt

Gretchen: How did your writing career begin? What was your inspiration for The King of the Trees?

William: I have always been a writer, even before becoming a Christian in college. In high school, I helped my father edit his card deck field guides to edible and poisonous plants. That was my first entry into the arcane world of publishing. Later, at Oregon State University, the professor of an English lit class I was taking convinced me to switch my major from biology/mycology to English. I’ve never looked back.

Soon after I accepted Christ as my Savior, God planted the seeds of The King of the Trees in my heart. I wanted to combine the best qualities of C.S. Lewis’s and Tolkien’s works, incorporating Lewis’s allegory with Tolkien’s extensive cosmology and use of invented language. (I also wished to create a fantasy that didn’t revolve around the occult—and to portray God’s power as being preeminent.)

I started this journey using my mother’s old manual typewriter to crank out a few pages, mainly during Christmas vacations. Later, I bought an electric typewriter and produced more of the story. Subsequently, while working as an interpreter and research associate at the University of Illinois, I resorted to scribbling my ideas for the first title in spiral notebooks during my lunch hours. By this time (1985-1987), I had graduated from Western Oregon University with my Master’s degree in deaf education, was married, and had two young children. I filled an entire cardboard box with those notebooks before I shelved the project for about ten years to raise my family and to work as an Assistant Professor at WOU.

I later left my profession to join YWAM with my family. It was then that I first realized a word processor could make my publishing dreams a reality. I’d been using a personal Mac to write and edit grants for WOU, so in the evenings after our YWAM classes were over, I would bang away on my Apple keyboard, creating an early version of The King of the Trees. When our YWAM stint was over, we were at a debriefing meeting when our leader asked, “At the end of your life, what would you regret not having accomplished?” I knew the answer was supposed to be, “Not having served God as a YWAM missionary,” but all I could think of was, I have to finish this book!

It took me more than twenty years to publish The King of the Trees. Subsequently, the sequels popped out every couple of years or so.

You’ve mentioned that you draw heavily on your own childhood in your first book, The King of the Trees. It’s also clear you have more than a passing knowledge of plant life and vegetation. Can you elaborate?

For one thing, my father and I kept bees, just as Rolin and his father are beekeepers in the first book. (For some reason, our bees liked to chase my father into the house, but they didn’t bother me much.) Dad also loved to prepare natural foods, including sourdough pancakes and oatmeal, which gave rise to Rolin’s favorite breakfast of oatcakes and honey. In addition to learning the Native American arts of making buckskin and rawhide, Dad enjoyed researching, gathering, and cooking wild edible plants of all sorts—and that pursuit rubbed off on me. Ultimately, my father’s avocations became his full-time vocation as a published author and outdoor survival instructor for the military.

Similarly, the references to mushrooms in the story stem from my lifelong fascination with those fungi. When I was twelve, field identification guides were just coming out, and my parents made sure my bookshelf was well stocked with the latest titles. I taught myself to use dichotomous keys for the purpose of mushroom identification. I’ve been picking and eating (and growing) mushrooms ever since.

This interest in fungi propelled me frequently into a local natural area of fifty-two acres that had been cut over when I was about six. Thanks to my father, I learned to identify the kinds of trees that were growing there. Even in high school, while most kids were working summer jobs, I was spending many hours exploring “the woods” and climbing the trees there. I loved soaking up the wonders of God’s creation, and I still do. I have always felt a special affinity for plants and trees, the way some people feel about animals, I suppose. Reading Tolkien helped cement that affinity.

Our family (and others in the neighborhood) successfully campaigned for those fifty-two acres to be preserved as a city park for hiking and nature appreciation. Springbrook Park is undoubtedly where my series first germinated, but I had to become a Christian to begin writing it. I’ve studied and planted Sequoia species for decades, so that genus was a logical choice for the Tree of Life. (Not to mention the fact that they are also among the tallest trees in the world.)

Many of the plants I refer to in The King of the Trees (and its sequels) are actual Northwest species, such as elderberries and morels (called “sponge mushrooms” in the book). Obviously, some of the species I describe are fantastical, such as the Torsil tree.

Would you tell us about The King of the Trees and its central metaphor?

The central metaphor in The King of the Trees (and in the series as a whole) is what I call the “Torsil Principle.” Torsils are trees that transport climbers into other worlds, not magically, but by a unique natural law.

In my books, a towering tree known as the “Torsil of torsils” leads not only to all of the God-figure’s created worlds, but also to His own home, a deathless paradise called Gaelessa, symbolic of Heaven. Since this Tree of trees is the only torsil to Heaven, it represents Christ. As Jesus said, “I am the way, the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father but by Me.” Moreover, the Tree gives its life for the salvation of all torsil worlds.

It’s important for readers to remember, however, that I’m not trying to remake Christ in the image of a tree, any more than C.S. Lewis was attempting to recreate Him as a lion.

Do you consider The King of the Trees allegorical fantasy? I’d love to hear your thoughts on how story can be used in communicating truth.

I definitely consider my first series to be a Biblical allegory. Particularly in the first title, The King of the Trees, most of the major characters and events can be interpreted symbolically—though the allegory is more subtle than what one finds in Pilgrim’s Progress. In other words, non-Christians can still enjoy the story line without appreciating the deeper spiritual implications.

Someone once contacted me to argue that “God does not work in a fantasy world.” However, allegorical fantasy can depict the tenets of the Gospel in ways that readers can more readily grasp. As Paul states in I Corinthians 9:20, it’s important to adapt the Gospel presentation to the cultural perspective of the audience, or as C.S. Lewis put it (in an essay in God in the Dock), “What we want is not more little books about Christianity, but more little books by Christians on other subjects – with their Christianity latent.”

The fact that C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien have millions of fans goes to show that fantasy is an effective medium for conveying truth—a quality that modern hearts yearn for. Let’s not forget that Jesus Himself used metaphor and hyperbole in His parables to communicate spiritual truths, as did many of the Old Testament prophets. In my case, the King of the Trees series is simply an extended metaphor or parable—and rousing good adventure, too.

You have written about how fantasy awakens “our dormant imaginations to the possibility of phenomena beyond the limited scope of our experience, enabling us to rediscover the world (and God) through fresh eyes.” I’d love to hear a summary of your thoughts on Christian fantasy.

Recently, I spoke at a Christian school. When I confessed that I had never read any of the Harry Potter books, the students practically sucked the air out of the room with a collective gasp. Young people love reading imaginative literature, but if we Christians are unwilling to produce it, then the world is always ready to fill that vacuum with dark, occult-themed titles.

I realize that the term “Christian fantasy” may seem an oxymoron to some in the faith, yet allegorical fantasy can effectively convey Biblical truths and steer young readers away from spiritual minefields. (Many young adults have told me these books changed their life.)

In my books, I scrupulously avoid the glorification of the occult while debunking magic. Because I hadn’t planned on writing sequels to The King of the Trees, I recapitulated the whole Bible in that title, from the Creation to the Second Coming, with Jesus being the central focus.

What are some of the fantasy books—beyond the works of Tolkien and Lewis—that have influenced you?

Years ago, I enjoyed Anne McCaffrey’s Pern series; however, those books didn’t have much impact on my writing. I don’t read fantasy any longer, since the genre has degenerated considerably since the days of Tolkien and Lewis. Much occult darkness has pervaded modern fantasy. I think it’s high time that the Christian community reclaims the fantasy/sci-fi genre for Christ!

My children are fascinated by the ballads and prophecy in poetry in The King of the Trees. Have you always written poetry?

Good question. I had written a little poetry (but mostly prose) before embarking on this series, but once I began writing The King of the Trees, the riddles and prophecies just poured out and flowed over into the sequels. It’s through this poetry that the God-figure mainly communicates with the human characters. (Typically, the characters must fulfill a prophecy or riddle that symbolizes the Word of God.) Most of these riddles are contextual. That is, they are intended to be read and interpreted within the context of the plot. In turn, they tend to drive the plot. A few of the poems could stand alone, however.

After writing a series of 7 fantasy books, you’ve changed genres. Tell us about The Creation Seekers series.

Book 1, The Lake Lights, is a YA sci-fi mystery/action novel set near my childhood home in Lake Oswego, Oregon. Thanks to his insatiable curiosity, Jonathan Oliver discovers two extraordinary phenomena that turn the scientific world upside down: one in a nearby abandoned iron mine, and the other right under his nose. To protect his discoveries, he must ward off an unscrupulous scientist bent on stealing Jon’s invention in order to sell it to the highest bidder. The plot blends fact and fiction, re-examining the old question, “Could dinosaurs still roam our planet?” In fact, this title was in part inspired by one of the creatures in Torsils in Time, which is Book 2 in the King of the Trees series.

Book 2, The Vikings of Loch Morar, is set both in Lake Oswego, Oregon—and in Scotland. This title is chock full of adventure, ancient history, Viking runes and Scottish riddles—with a dash of chaste romance. When a mysterious landslide and an unexplained lab accident nearly end Jon’s life, suspicion naturally falls on his old nemesis from Book 1. However, as in the Biblical account of Joseph, God turns to good what Jon’s enemies intended for evil. What makes this title unique is the colorful (and mostly true) history I weave into the plot as well as the use of Old Norse and Old Norse runes. It’s also a great introduction to Scottish idioms and accents, which are a knotty but fun challenge to convey on the printed page.

In The Lake Lights, you debunk Darwinism and make the case for the Biblical flood, as well as exploring cryptozoology (the search for hidden animals) and fossils, too. Tell us about your interest in paleontology and Creation Science.

Ever since my father took my brother and me on several fossil-hunting expeditions, I’ve been fascinated with those remnants of a bygone age. At the time, I accepted the conventional wisdom that they had formed millions of years ago. After becoming a Christian, I learned they are the by-product of the Genesis flood. I’ve been excited about Creation Science ever since. At one time, I even toyed with the idea of going back to school to study that unique discipline. After all, if Genesis is just a fable, then why did Jesus reference it on at least eight occasions?

For years, I have been deeply disturbed by the corrosive influence of evolutionism and old-earth chronologies on the Church and society as a whole. I’ve also been convinced that cryptid sightings around the world (such as Nessie in Scotland) represent creatures that survived the Genesis flood and have found suitable habitats in our modern world. Whether readers agree with me or not, I hope they will still enjoy relating to my characters, their predicaments and their triumphs.

What are some of the sci-fi mystery or action novels you’ve enjoyed reading personally, or with your children?

I don’t read much sci-fi these days for the simple reason that most of it is steeped in evolutionary theory. After all, the whole notion of alien beings is based upon the premise that if life could evolve here on earth, it could evolve elsewhere in the universe as well. Of course, there is no real evidence to support the alien-life proposition, though scientists continue to spend millions of dollars searching for signs of extraterrestrial sentient life.

That said, I did read a fair amount of sci-fi as a boy. In particular, I enjoyed the old Tom Swift series, which probably influenced my Creation Seekers series to some degree. As an adult, I’ve mainly read Clive Cussler, Tom Clancy, and Preston & Child.

While your first series is currently out of print, I know that you still have plenty of brand new copies waiting to be autographed and shipped to new readers. Can you tell us how we may most easily obtain your books—and let us in on any plans you have coming up?

After my original publisher went bankrupt, I was left with cases of new books, but no way to reprint them. That’s why when readers go to Amazon, they will find only third-party copies of my first series for sale—and KOT Books, LLC is one of those vendors. (That’s my publishing company.) When you purchase new copies through Amazon, more likely than not you will be dealing with me. (There’s no issue with buying the Kindle versions, of course.)

Frankly, it’s cheaper and easier just to obtain autographed copies via my website. I also offer the full set of seven titles at a steep discount that’s not offered anywhere else.

Eventually, I plan to reprint the entire King of the Trees series under my new “Creation Way Books” imprint, which is how the Creation Seekers series is being published. Speaking of the new series, both The Lake Lights and The Vikings of Loch Morar are readily available from my website, from Amazon (softcover, Kindle), from Barnes & Noble (Nook), from Google Play and Apple Books.

I am mulling over some plot ideas for a third title in the Creation Seekers series. The Vikings of Loch Morar left some loose ends to tie up. However, since I am helping my wife with her counseling practice (and because we now have four grandchildren), I’m no longer able to write full time.

Would you share with us what you believe to be the Christian fantasy Writer’s high calling?

Above all else, it is to polish the mirror of his craft until it flawlessly reflects the face of Christ. By imprinting his words with God’s truth, the storyteller both entertains and enlightens his readers with Lewis’s “latent Christianity.” For the staunch humanist, he can create untrodden landscapes where man is not the measure of all things, where every stone and leaf and breath of wind cries out, “He is risen!” And for the lost and lonely, the faithful fantasy writer will weave a glowing tapestry that depicts the Father watching over wayward sheep from the doorway of His Last Homely House.

“One of humankind’s most fundamental longings is to see the supernatural break through into the natural, to witness the miraculous in the midst of the mundane… This yearning arises not so much out of an escapist mentality, but from a hunger to assure ourselves that there is more to life than the purely tangible, that our earthly existence has a cosmic purpose.

“Fantasy tales serve this soul need by awakening our dormant imaginations to the possibility of phenomena beyond the limited scope of our experience, enabling us to rediscover the world (and God) through fresh eyes. In an age when scientific materialism reigns supreme as queen of isms, Christian fantasy puckishly invites us to peer beneath her tottering throne and find angels frolicking there.”

-William D. Burt in “Why Christian Fantasy?”

Photography: JenniMarie Photography

This review beautifully captures the spiritual depth and imaginative brilliance of The King of the Trees. Your thoughtful analysis offers valuable insight into how Christian allegory can be effectively woven into fantasy literature. Thank you for highlighting a work that enriches both the mind and the soul—your perspective is both enlightening and inspiring.

Thank you Gretchen for sharing these books! They’re going on my must-read list!

I think you’ll love them!

Magnificent job, Gretchen! This is the finest online interview anyone has ever crafted for me. I don’t know how you find the time to maintain this blog!

Why thank you, Bill. It was my pleasure. I really enjoyed getting to know you better, especially discussing your thoughts on fantasy.

(And yes, managing Kindred Grace definitely isn’t a full time focus for me but something I prioritize when I can.)